Complete seventeen page paper is available through email.

This report is the result of a "Topics Course" which completed my History Education classes at the Indiana University of Pennsylvania from the Spring 2006 semester.

The course of History 401 - "World War II Home Front" was conducted by Professor Elizabeth Ricketts-Marcus.

Italian American Racism During the WWII Era.

During the World War II era, Italian immigrants in America encountered harsh treatment from both citizens and the government. Prejudice paired with war time hysteria was directed at the Italian population and resulted in the internment of several thousand immigrants, executions of prominent businessmen, and the constant harassment of hardworking laborers. Many of these same people had sons discriminated against while fighting overseas in the United States military saving the world from fascism. Some victims cried “racism,” but for the most part Italian Americans pulled themselves up by their boot straps to make something out of their lives, despite the barriers. Nevertheless, injustices did occur, and at a critical time in world history the United States government treated Italians as second class citizens.

Most Americans considered the influx of these immigrants at the turn of the century as undesirable, and felt that they were eroding this country’s identity. At the time, the globe was sinking deeply into economic depression, and Italy was no exception. Similar to modern times, many emigrants chose to seek a better life elsewhere, rather than fix the problems in their own homelands. Italy was being dictatorially governed, primarily by ruthless and brutal gang lords whose government was characterized by violent feuds.[1] As instability met with financial downturn, American democracy began to look appealing. Men initially left home seeking work. Economically the conditions in Italy were so poor, that around nineteen hundred, one out of fifty citizens emigrated for the United States.[2] North America had yet to experience negative economic effects as harshly as Europe. These men hoped to secure employment and a stable home in the “land of opportunity.” Upon arrival, the immigrants found no welcome mat. No one befriended the cheaply working laborers who arrived seeking a better life than the ones they left behind in Italia.

Society’s View of the Italian

These new and darker faces found themselves at the bottom of the social totem pole. Italian newcomers were described as “low-class, ignorant, unassimilable, and prone to criminality.”[3] To make matters worse, the new immigrants practiced Catholicism. America was predominantly Protestant in the early nineteen hundreds, and earlier prejudices had developed toward the Irish who were also devout Catholics. Catholicism reinforced ethnic segregation, as each ethnicity practiced their faith in different parishes. The contradictions between the universal Roman church and the reality of ethnic division brought about tension in the United States among varying nationalities. Many Americans viewed this religion as a mixture of superstition, faith, and ritual. Tension developed as self-imposed ethnic segregation was viewed by Americans as an unwillingness to assimilate into “Americanism Ideals,”[4] or the idea of American cultural values.

Loading ships became the employment norm along the docks of New York’s harbors for many immigrants. This work was considered unappealing, difficult outdoor labor full of heavy lifting. Prior to legalized labor unions, ethnic groups banded together in employment. Undesirable dock work was usually reserved for Irish, Scotts, Poles, Slovaks, Italians, and other marginalized ethnic groups.[5] One source claims this experience is where the term “dago” originated. These various ethnic groups would negotiate agreements to load or unload cargo for ship captains; however, captains took advantage of the laborers by promising to pay the men on a given day. Often the ship would sail during the night prior to payday, leaving those laborers with nothing after a week of hard work. Quickly each of these various ethnic groups learned to demand “we get paid by the day or we go.”[6]

As with employment, ethnic groups congregated together in housing which was just as unfavorable. Once established, immigrants began sending portions of their wages home until enough money accumulated for their families to make the journey across the Atlantic. Initially, Italians were located in the Upper East Side of New York City living in tenement housing. Tenements were several story apartment buildings located in the overcrowded slums of a city. The Upper East Side was filled with the aroma of Italian cooking, and the streets with the sounds of organ grinders.[8] Inside the tenements, Italians left their doors open and socialized in the hallways, which was considered unusual by most other ethnic groups. Also considered unusual by other ethnicities was the Italian custom of a large family: on average each household contained eight children.[9]

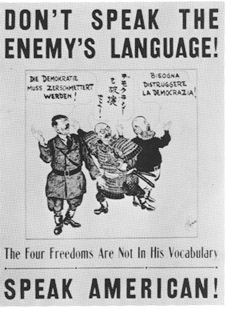

Unbridled prejudice within society resulted from the immigrant’s unconventional traditions, as commonly “alien cultures have been the recipients of scorn and maltreatment throughout much of American history.”[12] Though embracing democracy, Italian-Americans often found themselves defending Italy and its current fascist dictatorship as their beloved homeland most of whom hoped to return to one day. Xenophobia gripped the country’s mindset in 1939 as World War II loomed and threatened democracy worldwide. In addition, ethnic Italians were closely linked to organized crime, as criminality and dishonesty were considered part of the “cultural baggage of Italian immigration.”[13] Americans insisted that racketeering was not a native trait of America but was imported from Sicily and Naples. The government of Italy, led by Mussolini, was believed to be founded on such terrorism, and was considered a nationalized Mafia.[14]

The Americanism Ideal

Adolph Hitler viewed America as an inferior, mongrel, nation. Americans held a similar view of its Italian residents. The Italian segment of the population was even further dissected into groups of Northern and Southern immigrants. The Northern group was considered to be the lesser of two evils, due to their lighter “Aryan” skin tone. Some anthropologists argued that the Southern “Mediterranean” group possessed “inferior African blood…and demonstrated a moral and social structure reminiscent of primitive and even quasibarbarian times. They are volatile, emotionally unstable, soon hot, soon cool, and when they talk their hands will be moving all the time.”[15] Southern Italy’s location was viewed as a crossroads which joined Africa, Europe, and the East. Americans believed it had given birth to people with an “inherent racial inferiority.”[16] This led to discrimination against Italians based upon the worth of the province where the immigrant originated (with provinces further south being increasingly undesirable). This belief also led to the application of another derogatory term: “Guinea,” which originally meant an “inferior African slave, and their descendents.”[17]

Even in Italy countrymen were guilty of stereotyping themselves according to this cultural division, which was strangely familiar to our own mentality during the Civil War. Northern Italians viewed themselves as the industrious, wealthier, educated, sensible, and the stable half of the country. The southern Italians saw themselves as the agricultural, honest, hard working backbone of the country. They felt they were less conscientious but friendlier, warmer, and more sociable than the citizens from the north. The north viewed the south as disorganized, unreliable and impulsive. These views originated from a combination of historical and geographic factors. Granted there are economical, social, and cultural differences among Italian regions; but sociologists had not indicated until modern times that the personalities of both northern and southern Italians are remarkably similar, even during the emigration of the early 1900s for the United States.[17.5] Terracciano, Antonio. North vs. South: What's the Difference? Italian America magazine. The Order Sons of Italy in America, Winter 2010, page 8.

Most of the immigrants in the close-knit familial communities were illiterate laborers living at poverty level, which ultimately became a great advantage. As the depression set in, and wages decreased, many higher-paid Americans lost their jobs. However, the Italians, who were already at the bottom of the pay scale, continued working on the docks and in coal mines - among other unskilled employment. Additionally, Italians were accustomed to living inexpensively among large groups of family, this allowed for social mobility when the rest of the country suffered the effects of doing without. The playing field was leveled as the depression took its toll. Italians would work for bushels of potatoes, share crops, and share livestock to feed paesani and their own extended families.[18] As Italians continued to live relatively unaffected, they found themselves economically better off than the majority of the country, which eventually started to translate into some political rights. For the first time Italians began to hold public office and inspire the nation. Success was found by Italian Americans such as Congressman Fiorello La Guardia, Congressman Vito Marcantonio, Mayor Frank Rizzo, Mayor Joseph Alioto, boxer Rocky Marciano, Baseball star Guiseppe “Joe” DiMaggio, and many others.

War Time Hysteria

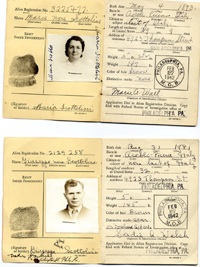

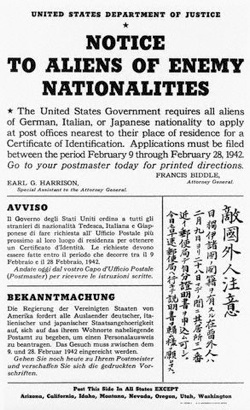

As America became involved in the war in 1941, hysteria made clear that the strides Italians had made during the depression were inconsequential. Society’s deeply rooted perception of the unscrupulous Italian immigrant resulted in Italian Americans being stigmatized as enemy aliens. Italian’s allegiance to America began to be questioned because so many immigrants did not take steps to complete the extensive requirements to become naturalized citizens, even though most had been here as long as forty years. Officials from the Justice Department and War Department were “convinced the Italians were under some kind of ideological spell from their fascist homelands.”[19]

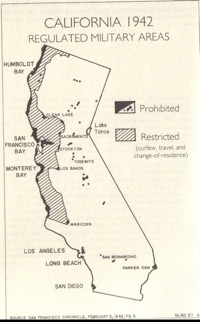

The Justice Department warned enemy aliens in mid December of 1941 that they would have to give up their firearms or be interned. Two weeks later they were forced to give up all cameras and radios.[24] Fears continued to make matters worse, as enemy aliens were barred from traveling any further than five miles from their home or work. Special permits to travel farther could be obtained for business use only. Vacations, entertainment, and pleasure trips were completely out of the question. Tensions became so bad that an official in San Francisco banned an Italian American woman from attending her friend’s funeral in the neig

Internment

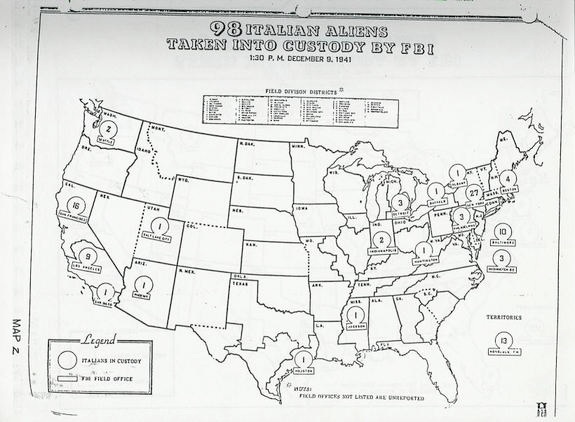

Perhaps the most notable violation of liberty was the internment of several thousand Italian immigrants during the war. In the United States, society’s fear led to the destruction of families, most of whom had enlisted sons fighting for America. This system

The major internment sites for Italian Americans were Fort George Meade in Maryland, Camp McAlester in Oklahoma, Fort Sam Houston in Texas, and Camp Forrest in Tennessee. Italian Americans were also sent to Fort Missoula, Montana; and any one of the forty-five other internment camps used by the Immigration and Naturalization Service and the Provost Marshal General's Office.[30]

Italian nationals saw for the first time the grim spectre of internment camps, mass evacuation of families, and the revocation of business licenses. These acts were similar to what the German and Japanese aliens of enemy descent had been experiencing. Doctors and dentists were forced out of work in a savage hunt to crush secret organizations which did not exist.[31]

Conclusion

The traditional injustices suffered by the Italian population typically served as motivation to improve their situation. Most families raised their children to work hard, appreciate what they had, and to speak English. Many of those children became successful members of society. Italians traditionally succeeded in America through hard work, perseverance, and without accepting government assistance. In July of 1942, President Roosevelt began to consider appropriating five million dollars from his presidential emergency fund to accommodate the Italian and German internees expected to be released over the coming months. In a silent effort to avoid national attention, signs were posted at the internment camp Post Offices announcing the release of all internees and the availability of federal aid. The federal aid was planned to fund housing and unemployment benefits; each detainee was eligible for twenty dollars of unemployment pay per week for twenty weeks. Of more than 3500 Italian American detainees only an estimated three hundred sought assistance. Richard Neustadt of the Social Security Board was warned by officials that Italians were too proud and would commit suicide before accepting government assistance.[34] They were correct. Italian Americans had a difficult time finding employment, and suicides were reported across the country. The greatest desire was for a man to provide his family with a better life than the one he had left behind in Italy. Ani Difrano is credited with having said, “The world owes me nothing. We owe each other the world.”[35]

Although the internment was behind them, prior to the war’s end in 1945 soldiers of Italian ancestry were treated differently than other soldiers. Jack Tabone recalled a meeting during the war with a high ranking officer. As Jack was escorted into the officer’s tent he was questioned about his loyalties to the United States and asked what he would do should he be ordered to march into Italy. In a related story of mistreatment, Private First Class Frank Vizza did not receive any medals for his heroic efforts in battle until President Ronald Reagan ordered a review of war records in 1984. Later that year Vizza was awarded the Bronze Star, Good Conduct Medal, European Theater Badge with Two Battle Stars, North African Theater Badge, Combat Infantry Badge for Sharp Shooting with Wreath, and the Victory Medal; all accompanied by a heart-felt letter of appreciation from President Reagan. When asked why it took forty years to be acknowledged, Vizza proudly responded, “No it wasn’t racism… when you are in combat things move so fast that the paper work gets lost for a while.”[36]

Due to members from the “greatest generation” one finds little or no prejudices directed to the Italian population in modern day society. This is partially the result of efforts from that generation assimilating into the culture and pursuing naturalization. Through perseverance and pride, Italians have virtually eliminated racism. By Refusing government assistance, tightening of their belts, and working hard, the first two generations of Italians gained success in America. As a final act of vindication, in 1999, as a result of lobbying by the Italian American community, the United States Congress addressed the treatment of Italian Americans during World War II. This resulted in House Resolution 2442, acknowledging that the United States violated the civil rights of Italian Americans during the war. The bill was passed in the House of Representatives in 1999, the Senate in 2000, and signed by President Clinton that same year.[37]

Italian Slurs and Slang Definitions

Condensed from above.

1. Tony - This was never a name. Immigrant luggage commonly read "TO: NY." To New York was frequently misinterpreted by clerks at Ellis Island to mean the name "Tony." Tony was then listed on the immigrant’s paperwork as their new name, since many could not speak English to correct the clerks, and the ones that could did not want to argue with a clerk that could deny them entry to the U.S., and make them get back on the boat to go home.

2. Dago - Various ethnic groups (Scottish, Polish, Irish, Italian, etc.) working at N.Y.'s docks would negotiate agreements to load or unload cargo for ship captains; however, captains took advantage of the laborers by promising to pay the men on a given day. Often the ship would sail during the night prior to payday, leaving those laborers with nothing after a week of hard work. Quickly each of these various ethnic groups learned to band together in makeshift "unions" and demand “we get paid by the day or we go.”

3. Wop - Derived from the Italian word "Guappo" meaning thug. Originally used to describe an Italian grape picker in Spain. Some sources cite an acronym meaning illegal alien: W.ith O.ut P.apers.

4. Guido / Guidette - Gino - Mario - A lower class/working class urban Italian immigrant. Popularized by MTV's "Jersey Shore" this is commonly now used to describe a loud, materialistic, arrogant, high maintenance, stereotypical New Jersey/Staten Island Italian American.

5. Goombah - Originally this was a term Italians used among one another when referring to a fellow associate from the same mafia. Today this is a derogatory term usually meaning fool or buffoon of Italian heritage.

6. Guinea - Originally meant an inferior African slave, and their descendants.

7. Paesan / Paesani - Typically, immigrants spoke regional dialects over English, and were loyal to kin or paesani (townspeople) originally from Italy.

8. M.A.F.I.A. - Mothers And Fathers Italian Association.

9. Spaghetti-bender / Organ-grinder. Worthless, Italian immigrant pandering for money.

During the early 1900s Italians were believed to have an “inherent racial inferiority.” This led to discrimination against Italians based upon the worth of the province where the immigrant originated (with provinces further south being increasingly undesirable). Northern Italians fit the "Aryan" skin tone with predominantly blond hair and blue eyes. The further south you go in Italy, the Italian was considered to have a "muddied" background from the crossroads of the world. Different cultures from all over the Mediterranean would trade or invade at different times in history, the result was dark hair, dark eyes, and darker, greasy skin. Most people from our area are Southern Italians who settled here to work in the coal mines.

Many local doctors would deliver babies and translate Italian names into German, or change them altogether to make them sound more "American" on the birth certificates. Dr. King and Dr. Bowser were local doctors who practiced this idea.

The Ku Klux Klan used to burn crosses in protest of Italian immigrants in Wishaw and the surrounding area.

Most immigrants who left Italy for America did not end up any better off than they were in Italy. In fact, many families ended up far worse off socially and financially.

Foot Notes

[1] Salvatore LaGumina, Wop! (New York: Quick Fox, Inc), 12.

[2] Stephen Fox, The Unknown Internment (Boston: Twayne Publishers), 9.

[3] LaGumina, 53.

[4] Dominic Pacyga, Catholics, Race, and the American City [Web site] (1997); http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=7579868548641; Internet; accessed 14 April 2006.

[5] Fox, 26.

[6] Wayne MoQuin, A Documentary History of the Italian Americans. (New York: Praeger), 46.

[7] Fox, 8.

[8] Kathy Peiss, Cheap Amusements. (Philadelphia: Temple University Press), 13.

[9] Peiss, 15.

[10] Jennifer Guglielmo, Are Italians White? (New York: Routledge), xi.

[11] LaGumina, 239-240.

[12] LaGumina, 14.

[13] LaGumina, 61.

[14] LaGumina, 256.

[15]Guglielmo, 9.

[16]Guglielmo, 9.

[17]Guglielmo, 11.

[18]Frank Vizza, interviewed by Phil Mennitti, History of Wishaw, Historical Society, 8 November 2004.

[19]Fox, 6.

[20]Fox, 2.

[21] Jack Tabone, interviewed by Phil Mennitti, History of Wishaw, Historical Society, 3 November 2004.

[22] LaGumina, 268-272.

[23] Fox, 47.

[24] Fox, 59.

[25] Fox, 62.

[26] Fox, 41-54.

[27] Fox, xi.

[28] Fox, 1.

[29] Fox, 156.

[30] Fox, 26.

[31] Fox, 43.

[32] Fox, 176.

[33] Fox, 59.

[34] Fox, 142.

[35] Guglielmo, vii.

[36] Frank Vizza, 8 November 2004.

[37] U.S Department of Justice, Report to the Congress of the United States: A Review of the Restrictions on Persons of Italian Ancestry during World War II [PDF file] (2001); http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/Italian_Report.pdf; Internet; accessed 7 February 2006.

Resources

Corbis. Web site. 2006. Available from http://www.pro.corbis.com/. Internet. Accessed 14 April 2006.

Fox, Stephen C. The Unknown Internment: An Oral History of the Relocation of Italian Americans during World War II. Boston: Twayne Publishers, 1990.

Guglielmo, Jennifer. Are Italians White? New York: Routledge, 2003.

Justice, U.S. Department of. Report to the Congress of the United States: A Review of the Restrictions on Persons of Italian Ancestry during World War II. PDF file. 2001. Available from http://www.usdoj.gov/crt/Italian_Report.pdf. Internet. Accessed 7 February 2006.

LaGumina, Salvatore J. WOP! A Documentary History of Anti-Italian Discrimination in the United States. New York: Quick Fox Inc., 1973.

MoQuin, Wayne. A Documentary History of the Italian Americans. New York: Praeger, 1975.

Pacyga, Dominic A. Catholics, Race, and the American City. Web site. 1997. Available from http://www.h-net.org/reviews/showrev.cgi?path=7579868548641. Internet. Accessed 14 April 2006.

Peiss, Kathy. Cheap Amusements. Philadelphia: Temple University Press, 1986.

Tabone, Jack. Interviewed by Phil Mennitti. The History of Wishaw. Historical Society, 3 November 2004.

Vizza, Frank. Interviewed by Phil Mennitti. The History of Wishaw. Historical Society, 8 November 2004.